G-7 leaders likely to focus on the war in Ukraine and tensions in Asia at summit in Hiroshima

The symbolism will be palpable when leaders of the world’s rich democracies sit down in Hiroshima, a city whose name evokes the tragedy of war, to tackle a host of challenges including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising tensions in Asia.

The attention on the war in Europe comes just days after Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy completed a whirlwind trip to meet many of the Group of Seven leaders now heading to Japan for the summit starting Friday. That tour was aimed at adding to his country’s weapons stockpile and building political support ahead of a widely anticipated counteroffensive to reclaim lands occupied by Moscow’s forces.

“Ukraine has driven this sense of common purpose” for the G-7, said Matthew P. Goodman, senior vice president for economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

He said the new commitments Zelenskyy received just ahead of the summit could push members of the bloc to step up their support even further. “There’s a kind of peer pressure that develops in forums like this,” he explained.

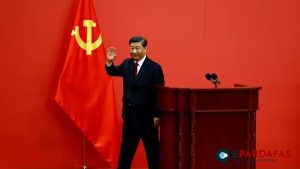

G-7 leaders are also girding for the possibility of renewed conflict in Asia as relations with China deteriorate. They are increasingly concerned, among other things, about what they see as Beijing’s growing assertiveness, and fear that China could try to seize Taiwan by force, sparking a wider conflict. China claims the self-governing island as its own and regularly sends ships and warplanes near it.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida also hopes to highlight the risks of nuclear proliferation during the meeting in Hiroshima, the site of the world’s first atomic bombing.

The prospect of another nuclear attack has been crystalized by nearby North Korea’s nuclear program and spate of recent missile tests, and Russia’s threats to use nuclear weapons in its war in Ukraine. China, meanwhile, is rapidly expanding its nuclear arsenal from an estimated 400 warheads today to 1,500 by 2035, according to Pentagon estimates.

Concerns about the strength of the global economy, rising prices and the debt limit crisis in the U.S. will be high on leaders’ minds.

G-7 finance ministers and central bank chiefs meeting ahead of the summit pledged to enforce sanctions against Russia, tackle rising inflation, bolster financial systems and help countries burdened by heavy debts.

The G-7 includes the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Canada and Italy, as well as the European Union.

That group is also lavishing more attention on the needs of the Global South – a term to describe mostly developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America – and has invited countries ranging from South American powerhouse Brazil to the tiny Cook Islands in the South Pacific.

By broadening the conversation beyond the world’s richest industrialized nations, the group hopes to strengthen political and economic ties while shoring up support for efforts to isolate Russia and stand up to China’s assertiveness around the world, analysts say.

“Japan was shocked when scores of developing countries were reluctant to condemn Russia for its invasion of Ukraine last year,” said Mireya Solís, director of the Center for East Asian Policy Studies at The Brookings Institution. “Tokyo believes that this act of war by a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council is a direct threat to the foundations of the postwar international system.”

Getting a diverse set of countries to uphold principles like not changing borders by force advances Japan’s foreign policy priorities, and makes good economic sense since their often unsustainable debt loads and rising prices for food and energy are a drag on the global economy, she continued.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will also be attending. His country, which is overtaking China as the world’s most populous and sees itself as a rising superpower, is playing host to a meeting of the much broader group of G-20 leading economies later this year.

For host Kishida, this weekend’s meeting is an opportunity to spotlight his country’s more robust foreign policy.

The Japanese prime minister made a surprise trip to Kyiv in March, making him the country’s first postwar leader to travel to a war zone, a visit freighted with symbolism given Japan’s pacifist constitution but one that he was under domestic pressure to take.

Another notable inclusion in Hiroshima is South Korea, a fellow U.S. ally that has rapidly drawn closer to its former colonial occupier Japan as their relations thawed in the face of shared regional security concerns.

U.S. President Joe Biden is expected to hold a separate three-way meeting with his Japanese and South Korean counterparts.

Sung-Yoon Lee, an East Asia expert at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, said that the meeting sends a message to China, Russia and North Korea of “solidarity among the democracies in the region and their resolve to stand up to the increasingly threatening autocracies.”

Biden had been expected to make a historic stop in Papua New Guinea and then travel onward to Australia after the Hiroshima meeting, but he scrapped those latter two stops Tuesday to focus on the debt limit debate back in Washington.

The centerpiece of the Australia visit was a meeting of the Quad, a regional security grouping that the U.S. sees as a counterweight to China’s actions in the region. Beijing has criticized the group as an Asian version of the NATO military alliance.

The decision to host the G-7 in Hiroshima is no accident. Kishida, whose family is from the city, hopes the venue will underscore Japan’s “commitment to world peace” and build momentum to “realize the ideal of a world without nuclear weapons,” he wrote on the online news site Japan Forward.

The United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, destroying the city and killing 140,000 people, then dropped a second on Nagasaki three days later, killing another 70,000. Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, effectively ending World War II and decades of Japanese aggression in Asia.

The shell and skeletal dome of one of the riverside buildings that survived the Hiroshima blast is the focal point of the Peace Memorial Park, which leaders are expected to visit.

(RSS/AP)

Comments