How to Avoid a US-China War (Interview with Kevin Rudd)

Kevin Rudd, a former prime minister of Australia, is President of the Asia Society and Chair of the International Peace Institute. This news interview is a part of regular column ‘Says More’ of Project Syndicate.

The title of your forthcoming book,The Avoidable War:The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict between the US and Xi Jinping’s China, refers specifically to “Xi Jinping’s China.” In a February 2020 commentary, you indicate why, observing that Xi wields “near-absolute political power.” Two years later, how have factors like the pandemic and real-estate scares affected Xi’s position? What is his biggest vulnerability?

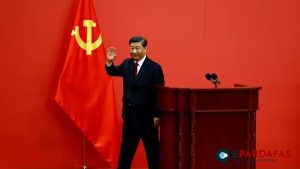

Xi Jinping is central to my book because it is simply impossible to understand fully what has happened to US-China relations over the last decade – and what might happen in what I call “the dangerous decade” ahead – without understanding both Xi himself and how he has transformed China since coming to power in 2012. The book dives into what drives him, and how he has secured such dominance in the Chinese system.

In the last two years, Xi has tightened his grip. In fact, at the Communist Party’s Sixth Plenum in November 2021, he secured one of his biggest political victories yet: the passage of a “historical resolution” officially placing him on the same ideological level as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. As of now, it looks fairly certain that he will be appointed to a third term in office at the 20th Party Congress this fall, effectively positioning him to be ruler for life.

But this does not mean that Xi is invincible. In the last two years or so, Xi has also been confronted by a number of challenges, the most serious of which is an economic-growth slowdown, caused partly by his own actions. Xi’s “pivot to the state” – including his obsession with “self-reliance,” the re-centering of state-owned enterprises, and legal and regulatory crackdowns on China’s most successful private firms (part of his “common prosperity” campaign) – has crashed into economic reality.

This misguided pivot, combined with problems like the deepening debt crisis in the property sector (which represents nearly a third of Chinese GDP), mean that Chinese growth may well decline significantly on Xi’s watch. That would deal a significant blow to his legitimacy. Already, one sees some remarkably frank dissent over his economic policy bubbling up from within the Party system. Still, it is impossible to tell how much real resistance Xi, a masterful political player, actually faces. At this point, there is no reason to assume he will lose his grip on power.

Given your expectation that Xi will be reappointed later this year, the need to understand what guides him is clear. In the same commentary – and, in more detail, in The Avoidable War – you break down his worldview into ten concentric circles of priorities emanating from the Party center. Which of Xi’s priorities do you think the United States does not understand well enough? Conversely, what are Xi’s biggest blinds spot vis-à-vis-the US?

There are a number of answers to your first question, but one idea I would highlight is Xi’s deeply held belief that, fundamentally, China is engaged in a life-or-death ideological struggle with the US (and its liberal democratic allies) over the future of the international order – and over the survival of the Communist Party of China (CPC). He is quite literal about this. For example, in July 2013, soon after taking office, he warned that “Western hostile forces” were intent on “Westernizing and splitting up China overtly and covertly,” that “currently, struggles in the ideological field are extraordinarily fierce,” and that “although [they] are invisible, they are a matter of life and death.”

But it is not only the US that is missing this crucial reality. The fact that Xi holds this belief, and views the world through such an ideological lens, is one of his blind spots. In any case, the US must recognize that it will not be able to convince China that it has good intentions. Only a firm, realist strategy of what I call “managed strategic competition” with China will be effective. Given its thirst for stability and predictability in the bilateral relationship, China also would most likely prefer this approach.

In our Year Ahead 2022 magazine, you warned that the US-China rivalry is now lurching toward a “Cold War-style nuclear arms race.” To mitigate the risks, you proposed starting with bilateral efforts to advance an arms-control agreement, but noted that “the eventual aim should be to pursue a multilateral arms-control agreement that at least includes Russia.” How might China’s increasing engagement with Russia – which, as you note in your book, China views as “almost completely on side” – affect any effort to secure a nuclear-arms agreement?

It’s going to make things very difficult, especially given what is now happening with Ukraine. The recent China-Russia joint statement, in which China explicitly sided with Russia in opposing NATO expansion for the first time, signaled very clearly that China is now willing openly to join with Russia in challenging the West. Together, they will resist any initiative that they view as constraining their strategic freedom of action.

But progress is not impossible. Both powers have a deeply realist foreign-policy culture; both are willing to accept agreements that are in their strategic interest, even if they are also in the strategic interest of the US. In any case, I always viewed a multilateral arms-control agreement as a long-term goal; it will be easier for the US to start with bilateral talks with China, including simply reopening channels of dialogue on this issue.

By the Way…

With the invasion of Ukraine, it seems that Russia could be included among the “unpredictable third-country variables” that The Avoidable War suggests could affect US-China relations during this “dangerous decade.” How might conflict in Europe affect Xi’s strategic calculations, particularly in Taiwan?

One thing is clear: conflict in Ukraine will not lead Xi hastily to launch an invasion of Taiwan. He has his own carefully considered long-term timetable on Taiwan, and is hardly going to let himself be rushed. In fact, I am fairly confident that we will not see large-scale military action against Taiwan during the 2020s. The military balance of power in the region is simply not where it would have to be for Xi to be completely confident of success, and given the political stakes, complete confidence is a prerequisite for action.

The 2030s, however, are a completely different ballgame. And, in the meantime, it is not inconceivable that Xi would use a European conflict to test a distracted America’s commitments in Asia with aggressive measures short of war, such as by declaring an air defense identification zone over the South China Sea.

A US-China relationship based on managed strategic competition – the approach you ultimately advise – would require, among other things, “the Taiwanese to take seriously their military deficiencies, which have accumulated over several decades, and which neither side of Taiwanese politics has so far demonstrated sufficient determination to resolve.” Which deficiencies are most urgent, and how can Taiwan address them without triggering a reaction from China

US and independent military assessments indicate that what would do the most to help Taiwan defend itself are the kinds of cost-effective asymmetric systems and measures that China itself has made an art of developing: anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles, portable anti-tank weapons, sea mines, and so on. Even more importantly, Taiwan needs well-trained, adequately supplied, and properly motivated military and paramilitary forces. All of this has been lacking, at least until recently, as politicians in Taipei placed a higher priority on flashy, big-budget systems – like advanced fighter aircraft and surface ships – that work better as political statements than useful tools for a high-intensity conflict with China.

Another key advantage of asymmetric systems is that they are inherently defensive, making it harder for China to claim provocation. That said, it is probably impossible for Taiwan to build up its military capabilities without triggering a negative response from China. As for the US, if it wants to help stabilize cross-Strait relations, curtailing visits by high-level government officials to Taipei – a routine practice during Donald Trump’s administration – would be a meaningful step.

Your book begins with the declaration, “I wish I did not have to write this book.” When did you realize that you did have to write it? Did the writing process make you more or less hopeful about the world’s prospects for sustaining peace?

The book in some ways flows from a report I wrote as a senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School back in 2015. It is also, in part, a response to a 2017 book, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, written by my friend, the Harvard professor Graham Allison.

I do not believe that war is inevitable – that’s why I put “avoidable” in the title. As I make clear in the book, I believe strongly that conflict is a choice, and history has shown that leaders have the agency to choose their own path for their countries. I dedicated the book to my children and grandchildren, because the path today’s leaders choose – the trajectory of US-China relations – will profoundly shape the century in which they grow up. At this point, fundamentally, I remain an optimist.

Comments