China makes promises to Bhutan, but has no plans to fulfil them!

Bhutan is a small landlocked country best known as the nation having introduced to the world the concept of Gross National Happiness.

However, of late, China has put so much pressure on Bhutan, by grabbing its territory that the people of Bhutan are not exactly happy with their northern Neighbour.

China’s territorial incursions in South Asia, and in particular Bhutan, has been making news recently. With its global hegemonic Endeavor in full active mode, China has been intimidating its smaller Neighbours into conceding valuable and culturally significant territories that are strategically vital for its global ambitions.

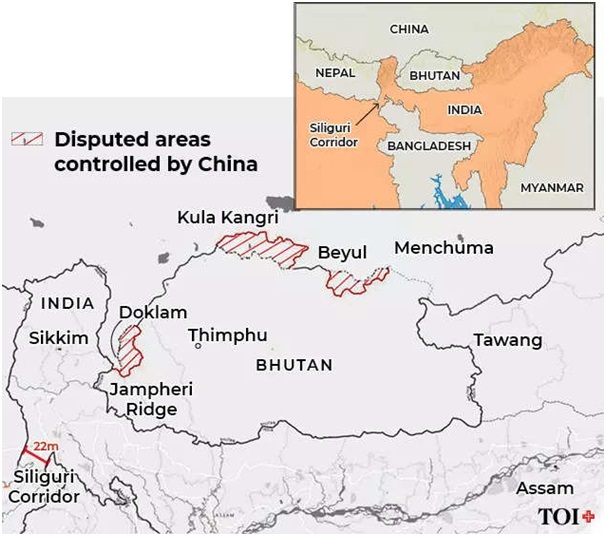

This is best exemplified by China’s strategy of negotiating with Bhutan to settle the boundary disputes, while continuing to claim more and more land inside Bhutan. This is the reality of China, which wants to gobble up Bhutan. One impact of this strategy is that it allows China to target India’s Siliguri corridor, a narrow geographical space that connects the mainland of India to its North-East.

China has shown an inclination to settle their dispute with Bhutan through the ‘Roadmap for Expediting the Bhutan–China Boundary Negotiations’ (Three-Step-Roadmap), an MoU signed in October 2021. This agreement came after a gap of five years in border negotiations, due to the Doklam crisis in 2017 and the covid-19 pandemic thereafter. Although there exists a long history of boundary disputes between the two countries, China in recent years has begun claiming more and more of Bhutanese territory to force it to toe the Chinese line.

The three-step roadmap lays down the process for speeding up boundary negotiations and more recently, both sides reiterated that the agreement reflected a ‘positive consensuses to push forward the implementation of the agreement for expediting negotiations to settle their border disputes. However, analysis of China’s negotiation strategies, shows that China intends to continue to grab more territory till such time that it becomes permanent, with no further requirement for talks!

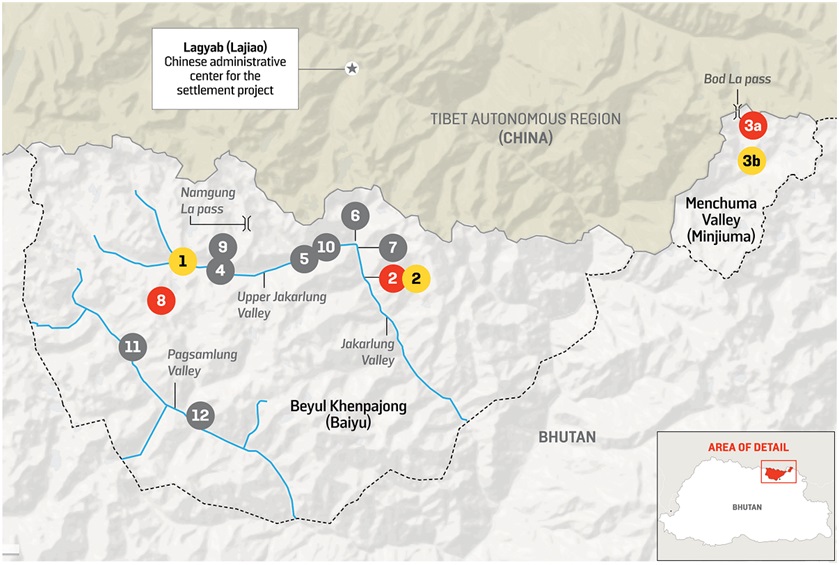

The two nations share a border spanning around 500 km in distance. Although the Bhutanese side claims that there persist only four territorial disputes, China has claimed around six ongoing disputes between Bhutan and China. In the north of Bhutan, China claims Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys, while on the other hand for Bhutan, these regions are of great cultural significance.

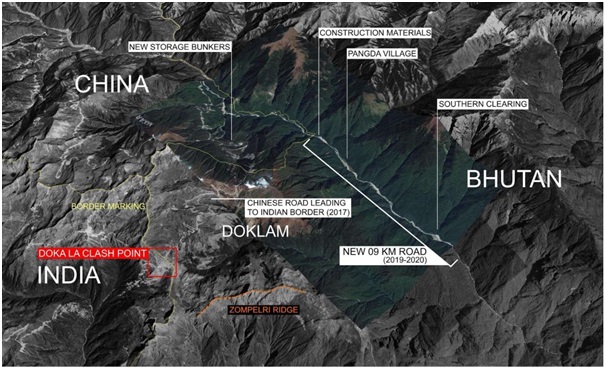

In the western front, areas including Doklam, Yak Chu, Sinchulungpa and Langmarpo valleys are amongst the few that are under dispute. It is important to note that some of these regions are quite close to the India, China, and Bhutan tri-junction and more importantly to the Siliguri corridor, which holds great strategic significance to India.

Over and above these claims, China had also laid its claim to Sakteng sanctuary located in eastern Bhutan, in 2020; one can only deduce that such claims are meant to be used as negotiation tools.

Apart from its shallow promises of attempting to settle the border dispute with Bhutan, China has also been infesting Bhutanese territory with settlements of villages (Xiaokang). According to recent reports, around 200 structures have been constructed in the region, with more constructions likely to come. These villages hold great advantage to the Chinese side, as many of them reside around the highly volatile Doklam region, close to the tri-junction bordering India.

These villages provide better troop reinforcement monitoring facilities amongst other strategic advantages to the Chinese side giving it an intelligence edge over its counterparts.

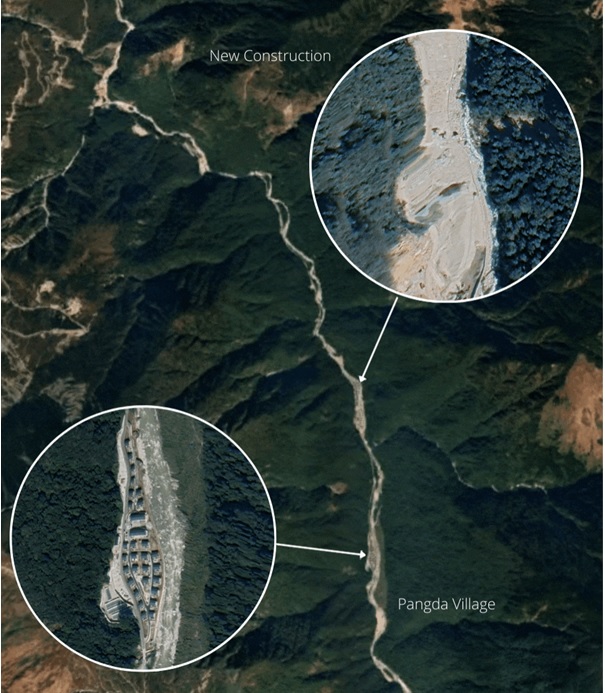

South China Morning Post (6 December 2020) reported that satellite images showed that China was developing Pangda village near Doklam, on the west bank of the Torsa River, 2.5km (1.5 miles) inside the Bhutanese border.

This location is very close to the tri-junction of India, China and Bhutan. In April 2020, the Communist Party secretary of the TAR, Wu Yingjie, travelled to the village of Gyalaphug, supposedly in TAR. He asked residents, all of them Tibetans, to “put down roots like Kalsang flowers in the borderland of snows” and to “raise the bright five-star red flag high.” As Foreign Policy (7 May 2021) points out Gyalaphug is in Bhutan. Wu and a retinue of officials, police, and journalists had crossed an international border. Chinese officials were in a 232-square-mile area claimed by China since the early 1980s but internationally understood as part of Lhuntse district in northern Bhutan.

Pangda and Gyalaphug are two of the 628 Xiaokang villages under construction by China along its border with India, Nepal and Bhutan. Let us face it. China is gearing itself to assert its control over Bhutanese territory. Pangda village for instance, appears to have been populated (Deccan Chronicle, 21 July 2022). Satellite images accessed by NDTV show that China is moving its men into the village to solidify its claim on the disputed territory.

The satellite images also show China is nearing completion of a second village and starting the construction of another village in the Amo Chu river valley. China has also been constructing villages around the Line of Actual Control in Arunachal Pradesh to beef up its defences and also to put pressure on India in the disputed area.

Bhutan is not the only country with which China has been raking up border disputes. The number of territorial disputes that China currently has stands at seventeen with its neighbouring countries; of which at least seven are territorial disputes relating to land.

Further, the South China sea dispute that China has with its Southeast Asian counterparts is a classic example of maritime claims made by Beijing to assert its stake over an entire region. Additionally, China’s economic presence in countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bangladesh has caused enormous economic instability and heightened the risks of debt there.

In its quest to become a regional heavyweight China has instead become an estranged ally that seems to be proving to its neighbourhood that it seeks only a dominant role, instead of carving a developmental future within its close neighbourhood.

Comments