Indonesia could be in for a Sri Lanka type Debt Trap

A recent Nikki Asia report speaks of a new shock wave hitting the corridors of power in Indonesia. The Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (KCIC) railway in December 2022 had proposed adding another 30 years to its 50-year concession of a high-speed railway under construction in Java.

If the Indonesian government is unable to turn down the proposal, the railway would be under China’s influence until early in the 22nd century! This has caused concern in Indonesia of a debt trap situation like Sri Lanka, which was forced to lease Hambantota Port to China in return for debt relief.

Such a situation has also occurred in several countries in Africa. Funded with a US$4.5 billion Chinese loan, the project falls under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the KCIC rail line, claims a AidData report, has left Indonesia and many other countries saddled with a mountain of unreported debt.

Forty per cent of the rail project is owned by Chinese firms.

With that precedent and unfavorable economic conditions globally prevailing, a growing number of countries are increasingly wary of launching new projects with China. Indeed, China’s ambitious infrastructure projects have slowed in recent years.

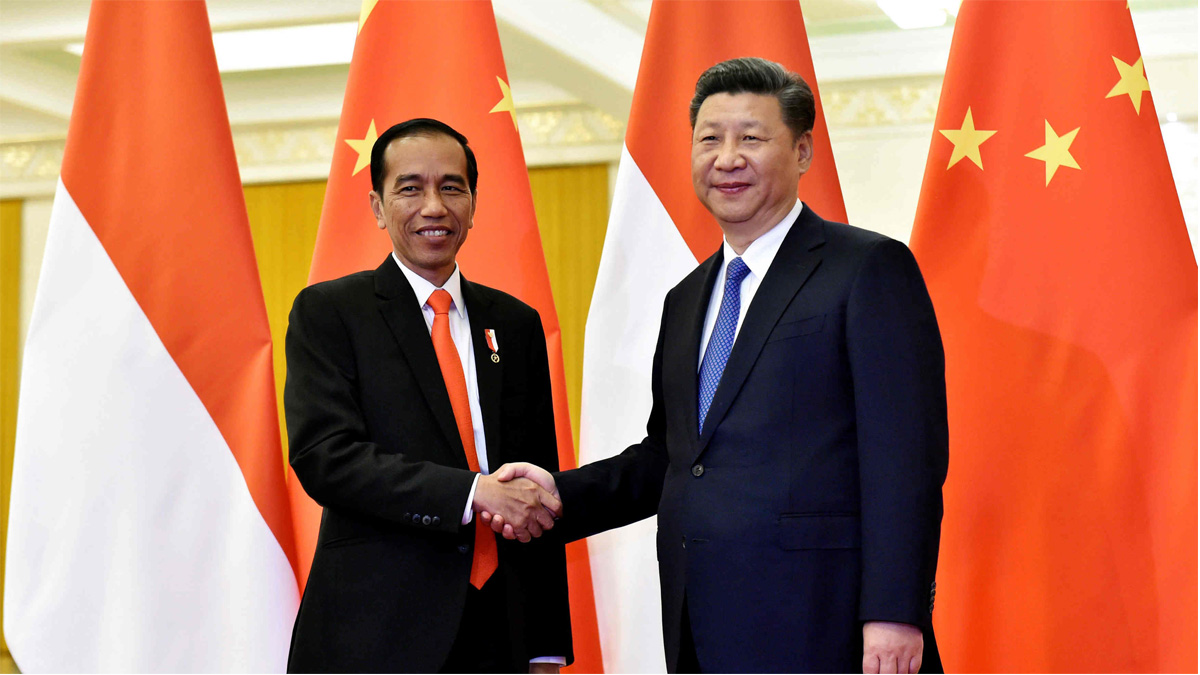

The background to this rail project indicates that President Joko Widodo had chosen China over Japan in 2015 to build the railway, with the date of completion set for as early as 2018, with trains to start rolling a year later.

However, construction remains ongoing and what appears to be a terminus station building in Jakarta is really a structure of reinforcing steel bars with a roof and nothing more. The delay has raised total construction costs by about 40 per cent, forcing the Indonesian government to raid state coffers for 7 trillion rupiah (US$468 million). More recently, there have been rumblings within the Indonesian government over the decision to go with China over Japan.

Indonesia has a 60 per cent stake in the PT Kereta Api Indonesia (KCIC) joint venture, comprising local partner PT Pilar Sinergo BUMN Indonesia (PSBI) and a Chinese consortium made up of China Railways International Co Ltd and four other companies.

The South China Morning Post reports that the complicated and time-consuming land acquisition process for the project wasn’t completed until 2020, as landholders along the route resisted selling, causing cost of compensation to rise steeply. Inadequate government planning probably caused other completion delays and cost overruns. Both Japan and China had bid for the contract, but it eventually went to China Railway Group Limited in 2015 after a period of intense lobbying and back-and-forth negotiations that saw the Chinese side ultimately drop its initial requirement for the Indonesian government to guarantee the project’s debts, in favour of a business-to-business agreement. China Development Bank offered loans to cover 75 per cent of the project’s cost with a 40-year repayment term, and completion was promised in time for the 2019 general election in Indonesia.

The rail project in Jakarta is one example of the larger challenge that Indonesia faces as far as Chinese investments are concerned. The AidData report shows that China committed more than US$34.9 billion in financial aid to Indonesia between 2000 and 2017, designated as either official development assistance or other official inflows. AidData also reports that Indonesia has US$4.95 billion of sovereign debt exposure to China and US$17.28 billion in what they call “hidden” public debt, which has been incurred by state-owned companies or other government entities without sovereign guarantees.

This implies that some 78 percent of Indonesia’s debt to China is not reflected in government’s books, amassing what a Koran Tempo online digital newspaper editorial has ominously described as a “ticking time bomb” that could impact the nation’s economic development.

Southeast Asia’s largest economy has over the years increased its debt to China and has increased the use of the Chinese yuan in its foreign transactions. As Indonesia becomes more reliant on China, it will find it more difficult to counter China’s growing aggressiveness in the South China Sea.

This is a major geo-strategic implication of Chinese penetration of Indonesia. For instance, Chinese fishing boats have often trespassed on Indonesian territory in the South China Sea. Yet Indonesia’s relationship with China has prevented it from acting aggressively knowing fully well that any aggressive step risks losing Jakarta’s largest trading partner and largest investors.

Chinese President Xi Jinping had announced the Belt and Road Initiative(BRI), more than a decade ago, as a massive infrastructure programme whose aim was to spread Chinese products and influence around the globe. Since then, more than 150 countries, hungry for funds and infrastructure, have concluded deals with China.

Over time, however, friction has been growing between many of these countries and China. In 2020 and 2021, many nations began to re-negotiate the loan terms of forty BRI deals. According to an estimate by the US-based Rhodium Group, this number represents an increase of 70 per cent from the previous two years. Another study found that China had spent US$240 billion just bailing out 22 countries (2008-2021).

The Jakarta Post concludes that Indonesia could pay dearly for its “take it lightly” attitude and the damage caused by the country’s negligence in the contract negotiations on the rail project. Domestic factors have thus also had a role in the delay and cost overruns as seen above.

Comments