Metal-mining pollution impacts 23 million people

At least 23 million people around the world live on floodplains contaminated by potentially harmful concentrations of toxic waste from metal-mining activity, according to a study.

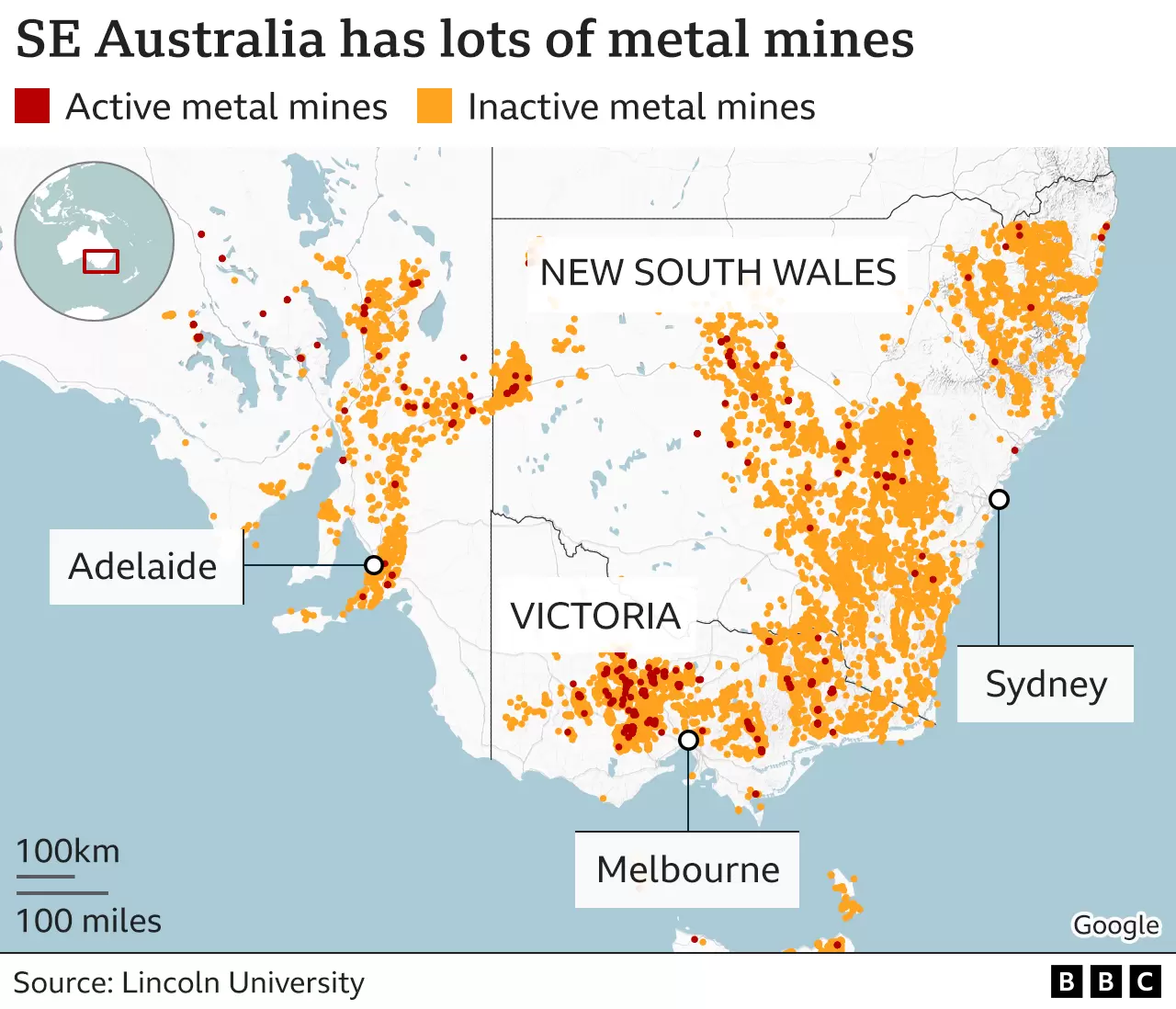

UK scientists mapped the world’s 22,609 active and 159,735 abandoned metal mines and calculated the extent of pollution from them.

Chemicals can leach from mining operations into soil and waterways.

The researchers say future mines have to be planned “very carefully”.

This is particularly critical as the demand surges for metals that will support battery technology and electrification, including lithium and copper, says Prof Mark Macklin from the University of Lincoln, who led the research.

“We’ve known about this for a long time,” he told BBC News. “What’s alarming for me is the legacy – [pollution from abandoned mines] is still affecting millions of people.”

The findings, published in the journal Science, build on the team’s previous studies of exactly how pollution from mining activity moves and accumulates in the environment.

The scientists compiled data on mining activity around the world, which was published by governments, mining companies and organisations like the US Geological Survey. This included the location of each mine, what metal it was extracting and whether it was active or abandoned.

Prof Macklin explained that the majority of metals from metal mining are bound up in sediment in the ground. “It’s this material – eroded from mine waste tips, or in contaminated soil – that ends up in river channels or [can be] deposited over a floodplain.”

Prof Macklin and his colleagues used previously published field and laboratory analyses to work out how far this metal-contaminated sediment moves down river systems.

That data allowed the scientists to produce a computer model that could calculate the extent of river channels and floodplains around the world that are polluted by mining waste – both from current and historical mining activity.

“We mapped the area that’s likely to be affected, which, when you combine that with population data, shows that 23 million people in the world are living on the ground that would be considered ‘contaminated’,” said Chris Thomas, who is professor of water and planetary health at the University of Lincoln.

“Whether those people will be affected by that contamination, we simply can’t tell with this research, and there are many ways that people may be exposed,” he stressed. “But there is agriculture and irrigation in many of those areas.”

Crops grown on contaminated soils, or irrigated by water contaminated by mine waste, have been shown to contain high concentrations of metals.

“With climate change and more frequent floods,” Prof Macklin added, “this legacy [pollution] is going to extend and expand.”

Prof Jamie Woodward from the University of Manchester, who was not involved in the study, said the research highlighted the threat posed by “silent pollution” stored in flood-plains.

“A good deal of river monitoring is focused on water when the real ‘nasties’ are often associated with river sediments,” he told BBC News.

“We need to better understand how contaminants are transported in the environment and where they are stored. This allows us to assess hazards and to mitigate against them. Heavily contaminated flood-plain grasslands should not be used for livestock grazing, for example.”

The researchers point out in their study that metal mining represents “humankind’s earliest and most persistent form of environmental contamination”. Waste from mining began to contaminate river systems as early as 7,000 years ago.

BBC

Comments