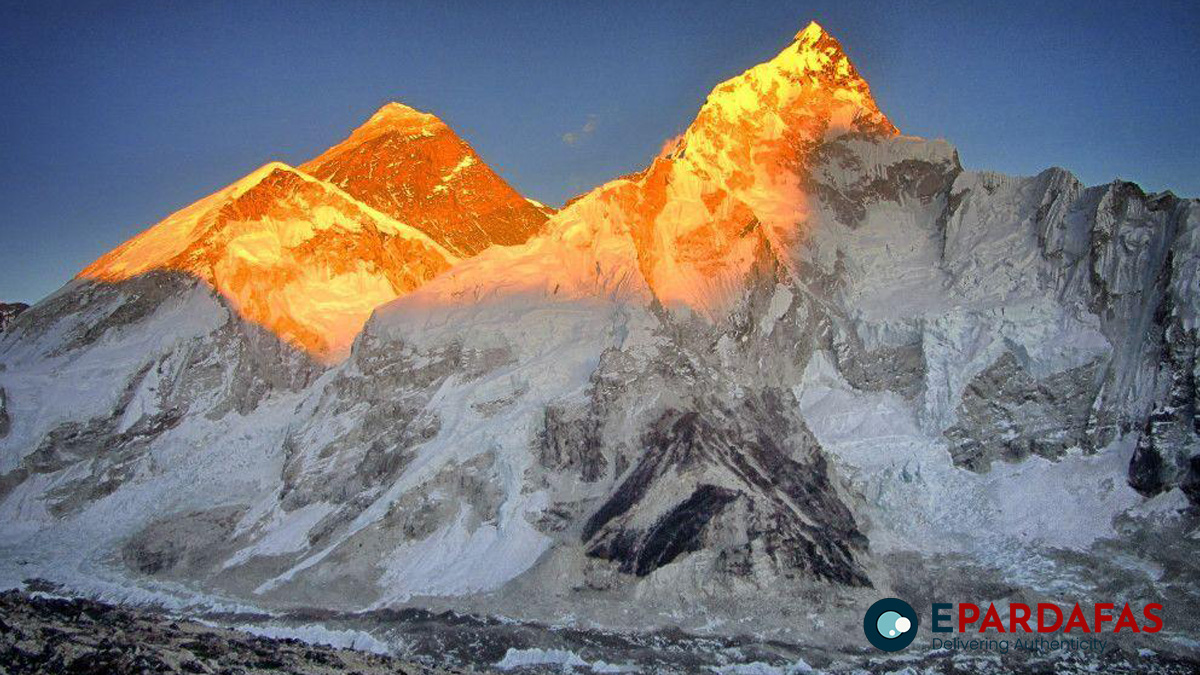

Mount Everest: Earth’s Tallest Mountain Is Still Growing, Thanks to an Ancient River Merger

Towering 5.5 miles (8.85 km) above sea level, Mount Everest is not only Earth’s tallest mountain but also a geological marvel that continues to rise. While the Himalayas have been gradually uplifted since their formation around 50 million years ago due to the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, new research reveals that Everest’s growth is not solely a result of this tectonic activity.

Scientists now believe that a monumental merger between two ancient river systems, which occurred approximately 89,000 years ago, has contributed to the mountain’s continued rise. This discovery adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of the processes that shape the world’s most iconic peak.

The Role of the Kosi and Arun River Merger

According to the study, published in Nature Geoscience, the merger of the Kosi and Arun rivers has led to accelerated erosion in the region around Everest. This erosion has carried away significant amounts of rock and soil, decreasing the weight pressing down on the Earth’s crust near the mountain. As the land lightened, the Earth’s crust has undergone a process known as isostatic rebound, causing Everest and neighboring peaks to rise further.

Researchers estimate that this river system merger has contributed an additional 49-164 feet (15-50 meters) to Everest’s height over thousands of years, translating to an uplift rate of about 0.01-0.02 inches (0.2-0.5 millimeters) annually.

What Is Isostatic Rebound?

Isostatic rebound occurs when the Earth’s crust, which “floats” on the semi-liquid mantle beneath, rises after a heavy load is removed. “Isostatic rebound can be likened to a floating object adjusting its position when weight is removed,” explained Jin-Gen Dai, a geoscientist at China University of Geosciences in Beijing and one of the study’s lead authors. “When a heavy load, such as ice or eroded rock, is removed from the Earth’s crust, the land beneath slowly rises in response, much like a boat rising in water when cargo is unloaded.”

This process is not unique to the Himalayas. For example, parts of Scandinavia are still rising due to isostatic rebound thousands of years after the last Ice Age, when thick ice sheets melted and reduced the weight on the land.

Everest’s Unceasing Ascent

The study’s co-author, Adam Smith, a doctoral student in Earth sciences at University College London, noted that GPS measurements have confirmed Everest’s ongoing ascent. While surface erosion caused by wind, rain, and river flow gradually wears down the mountain, the rate of uplift from isostatic rebound outpaces these erosive forces, meaning Everest continues to grow.

The research suggests that about 10% of Everest’s annual uplift can be attributed to isostatic rebound, while the remainder is due to the ongoing tectonic collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates.

This uplift also affects other Himalayan peaks. Lhotse, the fourth-highest mountain in the world, is rising at a rate similar to Everest. Meanwhile, Makalu, the fifth-highest peak and located closer to the Arun River, is experiencing an even higher rate of uplift.

A Living, Dynamic Planet

“This research underscores our planet’s dynamic nature. Even a seemingly immutable feature like Mount Everest is subject to ongoing geological processes, reminding us that Earth is constantly changing, often in ways imperceptible in our daily lives,” said Dai.

Earth’s outer crust is composed of colossal plates that move over time, a process known as plate tectonics. The Himalayas, including Mount Everest, were formed when the Indian plate collided with the Eurasian plate, and they continue to rise due to this collision.

More Than a Mountain: Everest’s Cultural and Global Significance

Mount Everest, known as Sagarmatha in Nepali and Chomolungma in Tibetan, straddles the border between Nepal and China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. It was named after George Everest, a 19th-century British surveyor.

However, Everest is much more than just a physical landmark. “Mount Everest occupies a unique place in human consciousness,” said Dai. “Physically, it represents Earth’s highest point, giving it immense significance simply by virtue of its stature. Culturally, Everest is sacred to local Sherpa and Tibetan communities. Globally, it symbolizes the ultimate challenge, embodying human endurance and our drive to surpass perceived limits.”

Conclusion

Even as Everest represents a peak of human ambition and exploration, it is also a dynamic and evolving feature of the Earth’s landscape. Thanks to the convergence of ancient rivers and the forces of erosion, this mountain continues to grow taller with each passing year, a testament to the ongoing geological processes that shape our world.

Input from Reuters

Comments