Rebuilding Syria After Assad

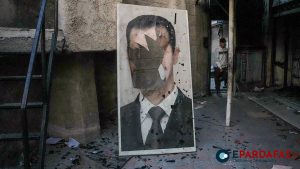

The rapid fall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad reflects the dramatic changes that have swept the strategic landscape of the Middle East in the past year. After civil war erupted in Syria in 2011, Assad clung to power for over a decade, despite facing a coalition of forces backed by the United States and Turkey. But only 11 days after the rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) launched its offensive, Assad fled to Russia, ending his family’s 50-year rule.

That outcome was the result of years of ineffective rule and economic and social hardship, with even the Alawi community that was Assad’s base of support defecting without a fight. The end came when his main external backers, Russia and Iran, also abandoned him, reflecting both countries’ profound weakening. Russia’s war against Ukraine continues to drain its resources and preoccupy the Kremlin, while Israel’s post-October 7 campaign against Hamas, Hezbollah (which provided significant support to the Assad regime), and Iran itself has crippled the Iranian-led “axis of resistance.”

Syrians will not miss Assad, a brutal ruler who failed his people. Many are celebrating in the streets, and refugees who have been sheltering abroad or in opposition-held pockets of Syria are starting to return to their homes.

The fall of Assad could also bring broader regional benefits. Assad’s regime facilitated the flow of arms from Iran to Hezbollah; new leadership in Damascus could further reduce Iranian influence and play a constructive role in shaping a more stable regional order.

But hope must be tempered by caution. Across the Middle East, the removal of strongmen has generally produced violent chaos, not stable and inclusive governance. During the Assad era, the Alawi minority ruled over a Sunni majority; revenge could be in the offing. More generally, Syria’s diverse population could easily fall prey to the politics of ethnic and sectarian division.

In fact, since well before Assad’s flight, Syria has been a state in name only. Its civil war divided the country into numerous fiefdoms that have been under the effective control of often hostile rival groups. One of those groups – Syria’s Kurds – is aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a terrorist entity, prompting Turkey to take control of a broad swath of Syria’s north.

Amid these existing fractures, extremist groups could capitalize on the fall of Assad and the resulting turbulence to strengthen their territorial footprint and power. That is what happened in 2014, when the Islamic State was able to seize control of a significant piece of Iraq and Syria as a result of the political mayhem in both countries. Extremist groups could now run the same play, which is why Israel has spent the last few days building a “security zone” beyond its border with Syria and destroying weapons stocks in the country to prevent them from falling into the wrong hands.

A case in point is HTS itself, which began life as an affiliate of al-Qaeda, and, like the PKK, is still designated by the United States and other countries as a terrorist group. While HTS’s leaders have pledged moderation and inclusiveness as they seek to fashion a national government, the group has a track record of repression. More broadly, Syria’s contending factions might seek to settle scores, not work together. Iran’s influence in Syria has plunged, but the Islamic Republic will try to retain its leverage as its former proxies – particularly the disenfranchised Alawis, a Shia sect – jockey with rivals for position.

In short, there is a great deal that could go wrong.

Looking ahead, Syria’s trajectory will depend first and foremost on its myriad players’ ability to achieve an inclusive political transition. Rebuilding a functioning state will require the restoration of Syria’s territorial integrity, which in turn will depend on the willingness of multiple territorial stakeholders to share power and sacrifice their autonomy in the interest of national unity. The other key challenge will be forging a new social contract that provides Syrians adequate levels of security and economic opportunity.

Syrians themselves must do most of the hard work, but the international community has an important role to play. For starters, drawing on the harsh lessons learned in Iraq, where the wholesale dismantling of the Ba’ath regime produced violent chaos, outside powers should press the newly empowered opposition groups to refrain from forcibly sidelining the Alawis, who formed the backbone of the Assad regime.

The prospects of a lasting settlement would significantly improve if the Alawi elite were adequately integrated into a diverse governing coalition. Moreover, Turkey and the US should press their Syrian proxies, the Syrian National Army and the Syrian Democratic Forces, respectively, to be constructive players and work with, not against, the transitional government.

Outside powers can also help prevent the further collapse of the Syrian state and its economy. Achieving a post-conflict settlement will become all the more difficult if the quality of life continues to deteriorate, and basic services like health care and education are unavailable. It was under precisely such conditions that regime change in Iraq produced radicalization and state failure.

The international community should therefore launch a multilateral aid program that combines humanitarian and financial assistance with capacity-building measures. As hosts to a large number of Syrian refugees, Turkey and the European Union have a keen interest in the early implementation of a multilateral strategy to foster the right social and economic conditions for the safe, voluntary return of the displaced population.

Assad’s fall has created an opportunity for the political and economic reconstruction of a key Arab state and the reshaping of its regional role. But the next few months are critical. The record of efforts to stabilize post-conflict societies in the region is littered with failure. Syria for the past 13 years is a case in point, as are Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. It is time to get one right.

Charles A. Kupchan is Professor of International Affairs at Georgetown University and Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. Sinan Ülgen, a former Turkish diplomat, is Director of EDAM, an Istanbul-based think tank, and a senior policy fellow at Carnegie Europe.

Comments