China’s 3-step roadmap is as trivial as its intention to settle disputes with Bhutan

China’s territorial incursions into South Asia has been making significant news since its global hegemonic endeavour began taking shape. With its economic might, Beijing has intended to intimidate its smaller neighbours into conceding valuable and culturally significant regions that could prove to be strategically vital for China’s global ambitions.

More recently the Chinese side had shown its inclination to settle their dispute with its peaceful neighbour Bhutan through the ‘Roadmap for Expediting the Bhutan – China Boundary Negotiations’ (Three-Step-Roadmap), an MoU signed in October 2021 between both the nations. The agreement came after a break of five years in border negotiations due to the Doklam crisis and the Covid pandemic. Although there exists a long history of boundary disputes between the two countries, China in recent years has begun claiming more and more of Bhutanese land in order to force Bhutan to toe the Chinese line.

The deal, which is also known as the 3-step road map, laid down the process for speeding up negotiation talks, and the agreement was recently reiterated by both sides as a ‘positive consensuses to push forward the implementation of the agreement for expediting negotiations to settle their border disputes. However, given the understanding of China’s negotiation strategies, it is important that China’s intentions be deciphered for what it truly stands to mean.

The two nations share a border spanning around 500km in distance, most of which has historically been disputed. Although the Bhutanese side claims that there persist only four territorial disputes, the Chinese government has claimed around six ongoing disputes between the two sides.

China for decades has claimed a significant amount of territory on Bhutan’s land. On Bhutan’s northern side Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys are regions China has laid its claim over, while on the other hand for Bhutan, these regions withhold great cultural significance. In the western front regions including Doklam, Yak Chu, Sinchulungpa and Langmarpo valleys are amongst the few that are under dispute between the two countries. It is important to note that some of these regions lay quite close to the India, China and Bhutan tri-junction and more importantly to the Siliguri corridor which holds great strategic value to India. Above and over these claims by China, it also laid its bizarre claim on Bhutan’s Sakteng sanctuary located in eastern Bhutan in 2020; one can only deduce that such claims are meant to be used as negotiation tools in the case of an eventual settlement that at present seems quite improbable.

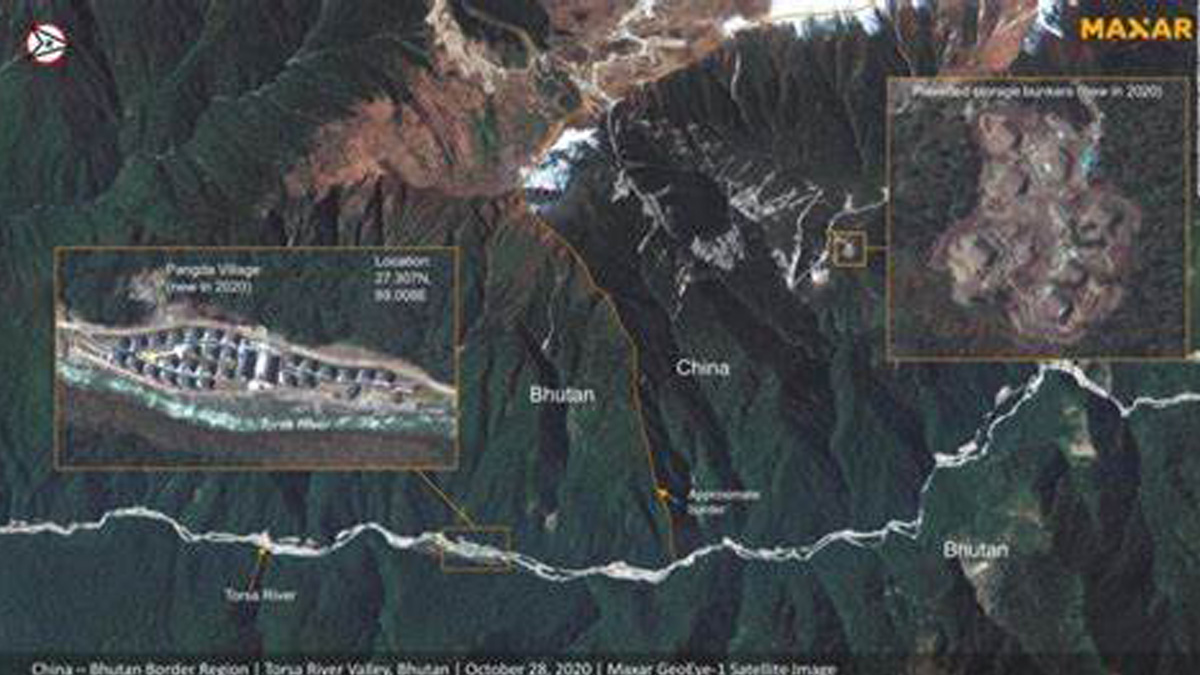

Apart from its shallow promises of attempting to settle border disputes with Bhutan, China has been, contrary to its publicly stated motives, infesting settlements of villages across the disputed regions. According to recent reports, around 200 structures have been brought up in the region with more constructions underway. These supposed villages withhold great advantage to the Chinese side as many of them have been seen to be taking shape around the highly volatile Dokhlam region closer to the tri-junction bordering India. These villages provide better troop reinforcement monitoring facilities amongst other strategic advantages to the Chinese side giving it an intelligence edge over its counterparts.

However, it is also important to note that India on various occasions made it clear to the Chinese side of the repercussions such unilateral altering of status-quo would inculcate as was showcased in the 2017 standoff.

Unsurprisingly, Bhutan does not seem to be the only country with which China has been propping up trivial border disputes. The number of territorial disputes from the Chinese side currently stand at an astonishing 17 disputes with its neighboring nations; of which at least 7 seem to be territorial disputes related to land cover, lest we forget the South China sea dispute that Beijing has ongoing with its southeast Asian counterparts. More so, China’s economic presence in countries including Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal and Bangladesh has caused enormous economic instability in these countries. In its quest to become a regional heavyweight China is rather becoming an estranged ally that seems to be proving to its neighborhood that it seeks only a dominant role instead of carving a developmental future within its close neighborhood.

Global ambitions for China begin by claiming a hegemonic position in its own neighborhood. Such aspirations are not only detrimental for South Asia as a collective region but are going to cause significant tussles in various other volatile sectors that China is attempting to claim its control over. A dominant global position must not come at the expense of peaceful small countries that do not wish to be part of the so-called ‘China’s rise’. These aspects not only reduce Beijing’s credibility but also in the long term will go on to prove to be consequential for China’s domestic politics as well. A failed neighborhood policy has consequential effects and China is on the trajectory of causing far more harm in a developing region than it could do good. Hence, countries in the region that assert their long-standing ally as a developmental partner must awaken to such damaging relations, for if not, China might very in the future claim its position as hegemon that stakes claim over sovereign decision making of matters that withhold national interests of independent countries.

Comments