Strong signal, pending action: Putin’s warrant shows limits of international law

By Laura Kelly

Russian President Vladimir Putin is a wanted man, but his chance of avoiding judgment is high.

It’s a sad realization for many who are looking to hold the Russian leader accountable for launching a full-scale invasion against Ukraine and face responsibility for unimaginable horrors allegedly carried out by Russian forces.

Still, global justice advocates say the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) arrest warrant against Putin for war crimes, served last week, sends a powerful message of deterrence and animates a debate over enforcement.

An arrest warrant was also served for Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights. Both were charged with the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia.

But there’s frustration over how the ICC, based in The Hague, Netherlands, can execute the arrest warrant.

Russia has rejected the ICC’s authority out-of-hand. Moscow is not a signatory to the Rome Statute that enshrined the court’s jurisdiction.

The forcible transfer of a population by an occupying power, in particular children, is a war crime under the Rome Statute.

Ukraine’s Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin said that they have succeeded in bringing back 308 Ukrainian children who were abducted by Russia, but estimates that Moscow holds more than 16,000 of these children.

In a program reportedly overseen by Lvova-Belova, these children are submitted for “reeducation” that in effect denies their Ukrainian identity and are handed over for adoption by Russian families.

Acting on an ICC warrant

The 123 members of the ICC are generally compelled to act on an arrest warrant if any of the alleged perpetrators travels to their countries. Still, they can refuse to act by citing domestic law, in particular if a country respects that a head of state enjoys unique protections and immunity from arrest.

Member-states South Africa and Hungary have already raised concerns over their commitments to the ICC.

“We can refer to the Hungarian law and based on that we cannot arrest the Russian President … as the ICC’s statute has not been promulgated in Hungary,” said Gergely Gulyas, chief of staff to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Reuters reported.

And South Africa’s international relations minister, Naledi Pandor, reportedly said Friday that the government is seeking legal advice over their obligations to the ICC if Putin arrives in Durban in August to attend the BRICS summit, the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Pandor said South Africa wants to “be in a position where we could continue to engage with both countries to persuade them towards peace.”

Mary Glantz, senior adviser for the Russia and Europe Center at the U.S. Institute of Peace, said South Africa’s response to the ICC warrant sends an important signal of the power of the court.

“I think the initial mood in the Global South was business as usual. The fact that they’re even investigating what legal obligations they have and that they’re thinking about this, I think is a positive step,” she said, referring to South Africa.

“It’s a step in the right direction that maybe we’re moving the needle a little on global public opinion about what’s going on in Ukraine.”

It’s an unusual move by the ICC to make public its arrest warrants, Gantz said, and is likely a signal of the court’s confidence in the evidence it has for its case, and that it may have other secret warrants for members of Putin’s inner circle.

“They could show up somewhere and that country, as a state party, could get the information that ‘nope, there’s an arrest warrant’ and they could be picked up,” Gantz said.

“It leaves a pall of uncertainty around everybody in [Putin’s] inner circle when it comes to international travel.”

America’s relationship with ICC

The war crimes warrant has also brought up uncomfortable questions for the U.S., which walks a fine line between voicing support for international justice and clashing intensely with the ICC over its pursuit of war crimes investigations allegedly by U.S. soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Biden administration has eased friction with the ICC by removing sanctions imposed on its chief prosecutor by the former Trump administration. The ICC, in turn, set aside investigations into alleged crimes committed by American forces in Afghanistan.

The U.S., which is not a member state of the ICC, has said the court’s most important function is to carry out justice in countries where the home courts are compromised, and that the strength of the American justice system should shield it from efforts to make it a target of the international court. Still, Congress has recognized the U.S. can do more and took recent action to amend U.S. law to better position itself to assist the ICC and apprehend alleged war criminals.

This includes the Justice for Victims of War Crimes Act, signed into law in January, which allows for America’s courts to carry out trials against alleged war criminals who are found to be in the U.S., even if they never targeted Americans or committed crimes in the U.S. The law is unlikely to be used to go after Putin, given the far-fetched scenario he’d travel to the U.S.

Another important piece of legislation, included in the 2023 funding bill, lifted a prohibition on the U.S. working with the ICC, but narrowly defined it to focus specifically on war crimes investigations surrounding Russia’s war in Ukraine.

“And so they changed it to say, ‘OK, for this very, very specific situation, there’s a certain amount of help we can give,’” said Celeste Kmiotek, staff lawyer with the Strategic Litigation Project at the Atlantic Council, which focuses in part on accountability for atrocity crimes and human rights violations.

“This is a very good opportunity for U.S. lawmakers to really consider, potentially being more open to the ICC.”

A delicate debate on U.S. involvement with the ICC is playing out behind closed doors between the Pentagon and the White House, the New York Times reported earlier this month, saying the Department of Defense is blocking the State Department from transferring war crimes evidence to the ICC.

The evidence reportedly includes material about decisions by Russian officials to deliberately target civilian infrastructure and related to the ICC’s case against Putin and Lvova-Belova.

On Friday, a bipartisan group of senators sent a letter urging President Biden to share U.S.-collected evidence with the ICC: “Knowing of your support for the important cause of accountability in Ukraine, we urge you to move forward expeditiously with support to the ICC’s work so that Putin and others around him know in no uncertain terms that accountability and justice for their crimes are forthcoming.”

A State Department spokesperson said that the administration has “worked hard” over the past two years to improve U.S. relations with the ICC, pointing to the lifting of sanctions and “a return to engagement,” but did not specifically address whether it is directly providing evidence to the international court.

Child relocation charges just the start?

The war crimes allegations over the forced relocation of children is significant, international law experts have argued, because it could lay the groundwork for more war crimes charges, including genocide and crimes against humanity.

There’s some optimism to believe Putin and his most senior officials will face justice.

Of the 18 heads of state or heads of major military forces wanted by international justice, 83 percent have faced accountability, Thomas Warrick, a nonresident senior fellow for the Atlantic Council wrote in an analysis.

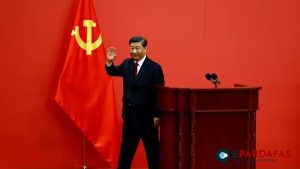

Putin has few friends left in the world. Still, support he receives from Chinese President Xi Jinping, and the comments from Hungary and South Africa highlight that the Russian leader is not entirely isolated.

But a larger rap sheet, possibly including genocide and other heinous war crimes, could help pressure action from countries who have stayed on the sidelines.

“You got to wonder, how many states really want to be seen standing side-by-side with an accused war criminal,” Gantz said, “somebody who is accused of kidnapping children, at this point, and could potentially be accused of genocide, which I think could be even more poisonous, even more toxic to people standing next to him.”

The Hill

Comments