The great Chinese thoroughfare: A handshake or backstab across the Himalayas?

Nepal, a landlocked nation tucked between China and India, has long experienced political unrest that has slowed the country’s economic growth. Poor economy, its location in a high-seismic zone and a lack of adequate infrastructure mean that Nepal is heavily dependent on foreign aid and investments for development, especially from its neighbors.

Historically, Nepal has shared very close and special ties with India that are conserved in the form of the India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950. However, the relationship has changed gradually since 2015. The earthquake of 2015 proved to be of significant importance from geopolitical and economic points of view for Nepal. In 2015, the rise of pro-China political figures and organizations directly intervened to affect Nepal’s foreign policy.

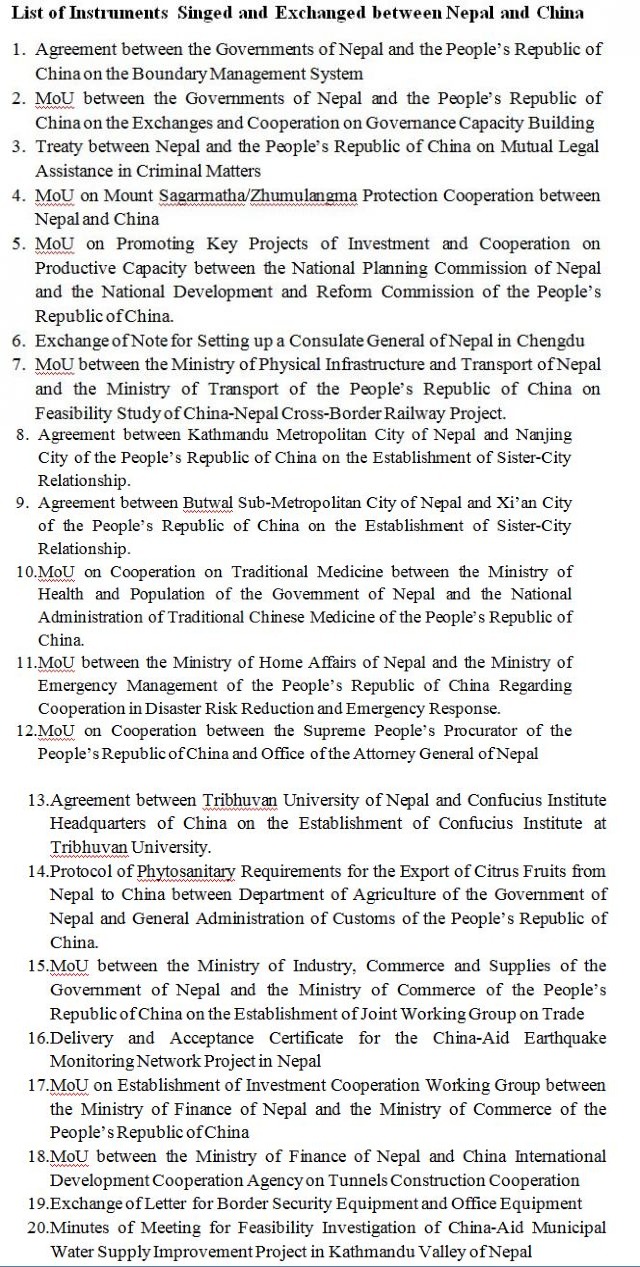

On one hand, the Nepalese government severed its relations with New Delhi, on the other hand, it welcomed Chinese aid and subsequent infrastructure projects with open arms. In 2016, Nepali Prime Minister KP Oli paid an official visit to Beijing and signed a series of significant agreements in areas of trade and transport infrastructure, financial cooperation, and borderland control.

Initiating a formal talk on Nepal’s inclusion in the BRI in 2015, China officially included Nepal as a part of its ambitious BRI project in 2017.

Under the BRI framework, Nepal proposed nine projects at the beginning of 2019. These included building new highways and tunnels, dams and railways as well as setting up a technical institution in Nepal. The most significant of these projects is the Nepal-China trans-Himalayan multi-dimensional connectivity system. The Connectivity Network prioritizes the operationalization of six economic corridors between Nepal and China with enhanced border facilities and advanced transport infrastructure. The trans-Himalayan railway would connect Kathmandu to Keyrung, a Chinese port, which would reduce Nepal’s dependence on India for a sea route.

While China claims that the BRI connectivity projects would help improve the Nepalese economy significantly, nothing could be farther from the truth. The reality is that the scale of trade between China and Nepal is not at all high. According to customs statistics, the total value of China’s foreign trade imports and exports to Nepal in 2021 was only 12.770 billion yuan, about 1% of China’s total foreign trade to South Asia. If Nepal imported Rs233.92 billion worth of goods from the northern neighbor in 2020-21, its exports across the Himalayas were valued at a mere Rs1 billion. The country exports mostly wool and metal handicrafts, woolen carpets and other handicraft items while importing electrical goods, machinery and parts, readymade garments, telecom equipment and parts.

These agreements paved a way for the Chinese to assert their influence in the country through education, tourism and other sectors. The Chinese government provides scholarships and sponsors study tours for Nepali students, civil servants and journalists. Mandarin has been introduced as a compulsory subject in schools across Nepal. A huge number of hotels, restaurants and other businesses are now owned by Chinese nationals.

The local population which is already suffering from rampant unemployment has expressed concern that the influx of Chinese will negatively affect their chance of employment. This has led to a large number of Nepalese citizens migrating to less densely populated areas in north and northeast India. A vast majority of these migrants are forced to take up odd jobs such as rickshaw pullers or waiters to make ends meet.

There have been some fabricated reports coming from Chinese scholars about emerging tensions between different ethnic and religious groups. Hinduism has been a major religion in Nepal since 1768 when it was established as the national religion of Nepal in the form of a constitution. However, in 2015, the Nepali government adopted a new constitution and became a secular state to promote multicultural development in the country. One of such papers claims that the Hindu majority has been marginalizing other religions such as Buddhists, Muslims and Christians as well as the indigenous Nepalese population to varying degrees. This practice has allegedly increased the gap and contradiction between different religious communities, threatening social harmony and stability in Nepal. Other Chinese scholars and academicians claim that the existence of ethnic and religious issues has given rise to the formation of various national liberation organizations in Nepal.

These anti-government groups have been allegedly engaged in violent terrorist activities which pose a great security risk to Nepalese society.

It is interesting to note that while these narratives are being spread on behalf of Nepal, China has successfully managed to mask the ulterior motives which these BRI projects serve in the region.

While the Chinese have been crying wolf about the security risk to Nepalese people because of the imaginary ethnic and religious conflicts, in reality, it is an unpalatable justification for introducing more and more security forces in the Nepalese territory. This practice is nothing new, for China has maintained a discreet military presence using private security companies in African countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Djibouti in the name of protecting its BRI infrastructure and people.2 The aforementioned paper adds, “Ethnic protests, terrorist activities and the risk of localized unrest in Nepal could adversely affect the operation of Chinese enterprises. The damage to infrastructure will have a direct impact on investor confidence and Chinese investors will need to invest more in strengthening security.”

It is worth noting that at present, China’s aid and investment are mostly concentrated in the northern part of Nepal, close to the Tibet autonomous region. This means that the security forces are also concentrated in that specific region. A question, a rather rhetorical one does arise – Is it a way to control the general Tibetan population and contain the “Tibet independence” forces in the region which pose a great challenge to China? One may find the answer in the fact that Nepal hosts the largest number of Tibetan refugees after India.

Time and again, Tibetans have expressed their concern over the massive construction of infrastructure like dams across their region by the Chinese who annexed the territory in 1951.

The tightening grip of Beijing means that the Tibetan population is constantly under surveillance, unable to move, speak or do anything freely in their own country. China has constructed hundreds of checkpoints along the borders of the ‘Tibet Autonomous region’, stopping any Tibetan emigrant from escaping to Nepal or India. For Tibetans, the Belt and Road initiative is synonymous with increasing Chinese pressure, influence and surveillance along with the degradation of the ecology and ‘Sinification’ of their religion.

The increasing presence of China in Nepal and Tibet has been a cause of concern for India. The new Nepal-China connectivity projects proposed under the BRI will not be limited to Nepalese territory but will also be extended to the Indian border. At present, there are two key trade routes—Rasuwagadhi-Kerung and Tatopani-Zhangmu (also known as Khasa)—between Nepal and China.

Kerung is situated at a distance of 190 km from Kathmandu while the distance between Tatopani and Kathmandu is 115 km.3 The road through Rasuwa from Keyrong remains the shortest route between China and India through Nepal at 265 km from Rasuwaghadi to Raxaul. The proposed trans-Himalayan railway project will connect Kerung in Southern Tibet to Nepal’s capital Kathmandu covering a distance of 170 km and eventually extending to India. This is an extension of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway to Kathmandu, which runs from Shigatse City, Tibet, through Jilong County, covering a distance of 72 km in Nepal in addition to the original 556 km.

The connectivity projects are of great military and political significance to China as they serve the dual goal of taming Tibet and reducing Indian influence in the region. Given its reputation for surveillance and intelligence gathering, China would certainly attempt espionage against India, posing a serious threat in terms of national security. In addition, the railway line would increase China’s strategic maneuvering space when tensions between India and China are on the rise.

While Nepal’s goals for development and economic growth are certainly ambitious, the ‘handshake’ with China could backfire, as it has for many other developing nations. Even if the Chinese media has made a concerted effort to dispel any worries equating the BRI projects with “debt-trap diplomacy”, the implications of Chinese funding for a small developing nation like Nepal are hauntingly real.

Comments